I first met Annamalai Swami in June 1993, during my initial visit to Arunachala and the Sri Ramanashramam. As I explained earlier, I was eager to meet with disciples of Papaji’s guru, Sri Ramana Maharshi, in the hope that they would be able to assist me in my predicament as a seeker and guide me further in my spiritual endeavor.

At the time of my visit, I was Papaji’s ardent disciple and one of his right-hand men. I was deeply grateful for the fact that through his presence and guidance, he had helped to recognize my true nature. He facilitated many dips into the Self during the time I was with him, but I was still not satisfied with my own awakening. In addition, I had doubts about several aspects of Papaji’s teachings. Annamalai Swami was the first of Papaji’s gurubhais that I sought out, hoping he could clarify these issues for me.

I wanted to hear more about the qualifications of the true guru, the necessity of practice, the initial recognition of the Self, and how the latter related to final enlightenment. I also wanted to determine if and how far Papaji had departed from his own guru’s teaching. I hoped that such an exploration would help me better understand my own teacher and myself. I was determined to ask my questions in a humble search for truth, and I was clear that I did not want to shed a bad light on my own guru, Papaji.

Let me be more specific about my dissatisfaction: Since I’d had my enlightenment experience with Papaji, my life hadn’t changed significantly. I still got angry and judgmental. At times I also found myself fearful, or immersed in desire or aversion. Obviously, I was not permanently happy and in peace. Foremost was the fact that I still had the desire for true enlightenment.

My meeting with the swami shortly after my arrival in Tiruvannamalai was preceded by an unexpected encounter that surprised and encouraged me. I was heading back to my lodgings in the Ramanashramam after an evening walk on the slopes of Arunachala, when I happened to pass a white bungalow in which fast, rhythmic music was playing. The familiar sounds stopped me in my tracks. I could hardly believe my ears—it was the music for Osho’s Dynamic Meditation! Somebody in Tiruvannamalai was practicing one of Osho’s meditations! Who could it be? I was overcome with curiosity and resolved to try and find out.

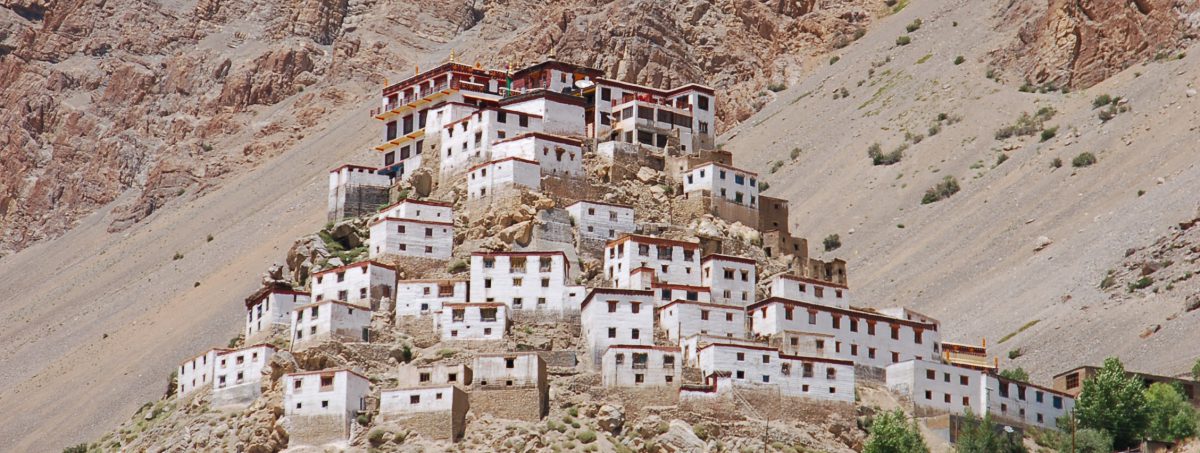

The entrance to the bungalow’s compound lay a few yards ahead of me along the path. It was marked by an iron gate set in an archway with an inscription identifying the place as the Sri Annamalai Swami Ashram. I passed quietly through the gate and followed the sound of the music. It led me to a wooded door at the side of the bungalow. It wasn’t locked. I opened it as quietly as possible, just enough to be able to take a peek inside. A lean, bearded man, clad only in a lunghi, had reached the third phase of the meditation. He was alone and oblivious to my presence. Smiling to myself, I closed the door softly and withdrew, walking back home through the gathering dusk. The next morning, when I took my seat in Annamalai Swami’s presence, I was surprised to find that his personal attendant and interpreter was the many I had seen doing Dynamic Meditation the evening before. Swamiji spoke only Tamil, the language of Tamil Nadu, his native state. His interpreter’s name, I learned was Sunderam.

I met with Annamalai Swami almost every day during my two-week stay at the Sri Ramanashramam, and Sunderam was always present as interpreter. Our exchanges were not recorded, but the conversation that follows represents a digest of our various encounters during that two-week period. I reconstructed it from memory shorty after our last meeting.

In daily life, Annamalai Swami was simply called Swamiji, and that’s how I addressed him in our conversations. In order to keep the interview in the same intimate climate that occurred in his presence, I will call him the swami, or Swamiji, in what follows.

Madhukar: Poonjaji told me that I have done whole work, that I have realized the Self. However, I still find myself confronted with questions and doubts about it.

Swamiji: Who has questions? Who has doubts?

Madhukar: Me . . . Now I suppose your next question will be: “To whom do doubts appear?” Right? [laughter] And I will answer, “To me,” and then I will need to continue to inquire, “Who am I?”—Sri Ramana’s self-inquiry.

Swamiji: That’s the right way to practice.

Madhukar: In my case, I have doubts about my realization in spite of Poonjaji’s assurance that it has really happened. My awareness of the Self is not without a break.

Swamiji: If there are breaks in your Self-awareness, it means that you are not a jnani [enlightened sage] yet. Before one becomes established in the Self without any breaks, without any changes, one has to contact and enjoy the Self many times. By steady meditation and the continued practice of self-inquiry, one will finally become permanently established in the Self, without any breaks.

Madhukar: How can I repeat the experience of peace and stillness that I often feel in Poonjaji’s presence?

Swamiji: Your experience of stillness is due to the influence of the milieu in which you find yourself when you are with your guru. However, your experience is momentary. Therefore, you need to practice until the experience of stillness is permanent.

Madhukar: Is the blissful and ecstatic state that I experience in Poonjaji’s presence samadhi [experience of the Self]?

Swamiji: Samadhi is perfect peace. But it is only momentary. Ecstasy arises when the mind comes back at the end of samadhi. It arises with the remembrance of the peace of samadhi. When the ego has finally died, the symptoms of bliss and ecstasy cease.

Madhukar: Poonjaji holds that no practice is necessary in order to realize the Self. You and Bhagavan Sri Ramana, however, contradict this stand quite clearly. To demonstrate this, I would like to read a quote from Sri Ramana. Is that okay?

Swamiji: Please, go ahead.

Madhukar: “In the proximity of a great master, the vasanas [latent tendencies of the mind] cease to be active, the mind becomes still, and samadhi [blissful experience of the Self] results. Thus the disciple gains true knowledge and right experience in the presence of the master. To remain unshaken in it, further efforts are necessary. Eventually the disciple will know it to his real being and will thus be liberated even while alive.”

Swamiji: I agree fully with Bhagavan. Bhagavan’s teaching is my own experience. I don’t know what Poonjaji is teaching.

Madhukar: As far as I have understood him, he teaches that self-inquiry needs to be done only once in the presence of the guru. In the first or perhaps second or third encounters with Poonjaji, the Self is realized. Papaji says that after the initial recognition of the Self, no further practice is necessary. However, he stresses that the guru’s presence and the association with him in satsang are usually required before that recognition can occur.

Swamiji: Only the serenity that is void of the ego is the highest knowledge. Until you attain the state in which you are the egoless reality, you must continue to seek the annihilation of the “I”-notion. This happens by associating with the teacher and by diligently practicing self-inquiry.

Madhukar: How long should one stay with one’s guru?

Swamiji: The association with the guru is necessary until the seeker has realized the Self. Only in the company of a teacher who has realized the Self can one become aware of one’s Self. Until you have realized the Self, you should study and practice the teachings of the guru.

Madhukar: What are the characteristics of a proper guru?

Swamiji: In the guru’s association or presence, you should find peace whenever your mind is attuned with him. He should have virtues like patience, quietness, forgiveness, and compassion. The one I whom you have faith is your guru. The one you feel a deep sense of respect for is your guru.

Madhukar: Although Poonjaji is my guru, I have met quite a few other gurus during my present stay at Arunachal. Is that okay? Is it okay to be in contact with more than one spiritual master?

Swamiji: Dattattreya had twenty-four masters. In fact, gurus can even be inanimate. Bhagwan’s master was Arunachala. The master is the Self. Through the grace of the guru, the seeker will come to know that Self which is true reality. Thus he recognizes that the Self is really his master.

Madhukar: While staying at the holy mountain, it becomes clearer to me with every passing day that I will have to leave my guru’s physical presence. However, the thought of leaving him makes me uncomfortable.

Swamiji: As I said, the Self is the reality, and the Self is the real master. So where could you go? You are not going anywhere. Even supposing you are the body, let me ask you, “Has your body come from Lucknow to Tiruvannamalai?” You simply sat in an airplane and in a car, and finally you say that you have come here. But you are not the body. The Self does not move at all. The world moves in the Self. You are only what you are. There is no change in you—the Self. Even if you depart from Poonjaji, you are here and there and everywhere. Only the surroundings change.

Madhukar: I am afraid perhaps to be missing out on Poonjaji’s grace.

Swamiji: Grace is within you. If grace is outside you, it is useless. Grace is the Self. You are never outside its operation. It is always there.

Madhukar – I have already told you something about my first teacher, Osho. I would like to share the most disturbing incident I had with him.

Swamiji: Please, don’t hesitate to speak. However, your doubts must naturally relate to the level of the body and mind and manifestation. They can only relate to what is unreal. Perhaps one day all your doubts will be removed once and for all—when you realize who you really are.

Madhukar – About six weeks before his own death, Osho’s lover and companion, Nirvano, took her own life in his ashram in Pune. She had lived intimately in Osho’s presence for almost twenty years. Her suicide shocked me more deeply than my guru’s death. It wasn’t just that she did not attain enlightenment; she must also have lived in a state of terrible misery and depression. My hopes of ever getting enlightened crashed with her death. I thought that if she, who had had such intimate contact with the master for such a long time, could not achieve enlightenment, then what chance was there for the rest of us? Her death quite disillusioned me.

Does her example demonstrate how difficult it is to become enlightened? And what about meditation? In her case, two decades of meditation practice failed to lead to enlightenment, and indeed it couldn’t even save her from committing suicide.

Swamiji: I can understand your feelings about the lady’s death and the conclusions you have drawn from it. Each person’s life evolves according to his or her destiny and karma [the law of retributive action] from the previous life. Everything that happens, happens according to the Supreme Power. An event in a devotee’s life does not occur because of the influence of his or her guru. It happens because it is so destined. Such an event has nothing to do with the ability or inability or power or powerlessness of the guru to govern events.

Take the example of Sri Ramana. In the 1920s, Bhagavan had a personal attendant who had served him for many years. He was called Annamalai Swami, like me. That devotee had the privilege of being in his master’s presence around the clock. At some point, he left Bhagavan and lived alone in the forests some thirty kilometers from here, because he thought he was not worthy to be near his master. Several times Bhagavan tried to bring him back to the ashram. He sent several people to fetch him. But Annamalai Swami refused to return. Instead, he committed suicide by hanging himself from a tree.

The swami’s narration shocked me. I felt deep compassion for these two devotees who couldn’t even be saved by the proximity of their teachers’ presence. I knew that further questioning about this topic wouldn’t help dissolve my pain. If anything could, it was nothing less than the presence of the Self. When Annamalai Swami finished narrating this story, we sat together for a long time in silence.

I returned to Arunachala six months later, in December 1993. My earlier conversations with Annamalai Swami convinced me that I had come to a spiritual impasse with Papaji. Consequently, I had decided to leave my teacher and return to the womb of his guru’s holy mountain.

Since Papaji had offered no further guidance, Annamalai Swami’s words during my earlier visit were a big help to me: “If there are breaks in your Self-awareness, it means that you are not a jnani yet. Before one becomes established in the Self without any breaks, without any changes, one has to contact and enjoy the Self many times. By steady meditation and continued practice of self-inquiry, one will finally become permanently established in the Self, without any breaks.” After researching Sri Ramana’s works, I came to the conclusion that Annamalai Swami taught what his teacher did. And that teaching was now being confirmed by my own experience. On the other hand, Papaji had established his own, unique teaching in this respect, which wasn’t congruent with my experience. I was now beginning to face this reality.

On my previous visit to Tiruvannamalai, I had considered myself still associated with Papaji as a student. However, on this visit, I felt I could ask other teachers questions without inhibitions. I wasn’t yet sure if I was looking for a new teacher. I stayed for six weeks, and during this time I had a further series of conversations with Annamalai Swami. The following talk was recorded on December 24, 1993 at the Sri Annamalai Swami Ashram. In addition to the swami, Sunderam, and myself, four other seekers were also present.

Madhukar: You lived with Sri Ramana Maharshi in the Ramanashramam from 1928 to 1938. After ten years of ashram life, you moved out and lived on your own. You chose to distance yourself physically from the Maharshi. I would like to know what made you stay away from Bhagavan while he was still in his body?

Swamiji: When Bhagavan entered my being, my life became natural, and so there was no need to stay with him. Bhagavan acknowledged this, and therefore I went on my own. When a flower becomes a fruit, there is no need for it to stick to the tree any longer.

Madhukar: From 1938 to 1993, for fifty-five years, Swamiji has been living in his own ashram. Is that right?

Swamiji: In the years 1938 through 1942, I was living on my own, but I was going for Bhagavan’s darshan on a daily basis. I was meditating with him every day.

On one occasion in 1942, Bhagavan covered his face with a cloth when I came for his darshan. I became very worried and I asked him, “Why have you covered your face as soon as you saw me? Does it mean that I should not come anymore, or what?” Bhagavan remained silent. He was not saying anything. After a while he said, “When I am just relaxed in my own Self, why do you come and disturb me? That is what I want to say.” I understood that Bhagavan did not want me to come to him any longer.

After I had left the hall and walked away for some distance, Bhagavan called me back and said, “If human beings don’t think of God or meditate on God or truth, they will live in misery and suffering. Similarly, if one has reached the state of maturity and if one—in spite of one’s maturity—keeps thinking that one is different from the guru or from God, such an attitude will produce the same suffering.”

These words made me understand that Bhagavan didn’t want me to come to the ashram anymore. He didn’t want me to come to see him any longer. He wanted me to stay by myself. That’s why I stayed by myself in Palakottu from that time onwards.

Madhukar: Was Bhagavan happy with your decision? Did he comment on it?

Swamiji: Not directly. He had his own way of communicating with me— like in another incident in which Bhagavan made it clear to me that I should stop seeing him. Bhagavan used to go for a walk on the hill almost every day. He was using the path which led past my hut in Palakottu. I used to go to the hillside to meet Bhagavan on his walk. True, Bhagavan had indicated that I shouldn’t meet him in the ashram anymore. But he had not told me not to come to the hill and have his darshan during his daily walk. I had thought that Bhagavan didn’t mind my habit. But when I met Bhagavan on this specific occasion on the hill, he asked me three times, “Why have you come? Why have you come? Why have you come?” Then he said to me, “Staying by yourself, you will be happier than me.”

Madhukar: Could you finally let go of his physical presence?

Swamiji: Yes. I did.

Oh! Now I remember another incident which happened before the one on the hill. One day, Bhagavan came to Palakottu. I saw him standing outside my hut. When I went outside to greet him and prostrate to him, Bhagavan said, “I have come for your darshan.” His words shocked me. I said to him, “Why is Bhagavan saying something like that to an ordinary man like me? Why is Bhagavan using big words like this? It is not correct to say things like this!” Bhagavan said, “You are living by my words. Is it not great?!”

Bhagavan told me that I did not need to go anywhere. He told me to just stay at my place in Palakottu. He told me just to be by myself. He told me just to be my Self. And he told me that whatever I will be needing will happen by itself. He said there is no need to ask anybody for money. “Money will come to you whenever it is needed,” he said.

Madhukar: Did his words come true?

Swamiji: Yes, in every respect. Bhagavan’s words all became true. And I did stop seeing him. Even on his mahasamadhi, I remained by myself— with my own Self.

Madhukar: I heard that Swamiji has never left Tiruvannamalai during the past fifty-five years. Is there a reason for this or did it just happen?

Swamiji: Bhagavan told me to stay at this place. I followed my guru’s words. I found that there is no happiness outside. So I stayed “at home.” There isn’t anything outside. Whatever you are seeking is your Self. Whatever you are seeking is the atman. That’s why there is no need to go outside. Bhagavan told me, “Don’t even go to your neighbor’s room.” So I didn’t.

Madhukar: But you used to do the thirteen-kilometer-long pradakshina [the practice of circumambulating a holy object] around Arunachala once a day, didn’t you?

Swamiji: Yes, I used to do that.

Madhukar: Are you still doing that practice?

Swamiji: No, nowadays I am not doing pradakshina anymore.

Madhukar: Let me tell you what I understand as discernment by means of inquiry:

A thought arises.

Now the “I” or the ego asks, “To whom does this thought arise?”

The answer is, “To me.”

The “I” then asks, “Who am I?” There is an “answer” that has no words.

Somehow, nothingness or silence is present. Nothingness or silence is there as an answer to the question “Who am I?”

Swamiji: Correct.

Madhukar – Is it necessary to keep asking, “To whom does this nothingness and silence appear?” When nothingness and silence “appear,” do I need to ask further?

Swamiji: As soon as you realize that there is only a rope and not a snake, you don’t need to keep questioning whether what you see is a snake or not. But you should not forget that there is only a rope.

Madhukar – Do you mean to say that there is no need to ask again, “To whom does nothingness appear?”

Swamiji: That’s right. There is no need for any further questioning, because there is no duality in that silence and nothingness. Silence and nothingness are not things you experience—they are what you are.

Madhukar – I am asking this question because it seems to me that there is duality. Isn’t it the “I” or the “I”-thought that is perceiving nothingness or silence? There is nothingness. But this nothingness or silence is still perceived by something that I think is the ego.

Swamiji: In that nothingness or silence there is no “I”-thought. That is real life. That is reality.

Madhukar – I am still not clear. Let me ask again: Is the perceived nothingness, or silence, perceived by the “I”?

Swamiji: Let us take an example. First you misunderstand yourself to be somebody else—not a human being. Some day you come to know that you are a human being. This understanding will always stay with you. After you have this understanding, what more do you need? So it is with the Self. Knowing the Self is being the Self.

Say you are Madhukar, but you think you are somebody else. Now you come to know that you had mistaken yourself to be somebody else; you have come to know that you are Madhukar. You realized that you were Madhukar before, but you just didn’t know it. Having come to know your true identity, there is no need to do anything further. Now you know you are Madhukar. There is only one Madhukar. Whatever exists is in a state of oneness. And in oneness there is no duality.

Madhukar – Swamiji, please clarify one more time for me: After asking “Who am I?” and “To whom does this thought appear?” there is simultaneously beingness or nothingness and the awareness of perceiving the object “nothingness.” If inquiry is done correctly, should there be only nothingness without the sense that an object called beingness or nothingness is perceived?

Swamiji: For whom does this duality exist?

Madhukar – For me. In Sri Ramana’s inquiry, the next question would be “Who am I?” In my case the “answer” is a nothingness and silence without words. The sequence is, “To whom does this nothingness, this silence, appear?”

“To me.”

“Who am I?”

“Nothingness, silence.”

So you can see, my situation is like a dog biting its own tail. There seems to be no way out of the circle. How should I proceed with my inquiry practice?

Swamiji: You are Madhukar, you know that. After you have come to know that, why do you repeat that you are Madhukar or why do you forget that you are Madhukar? Be Madhukar! You are Madhukar. Knowing that you are Madhukar, you are Madhukar. At the moment of recognizing that silence and nothingness as your Self, you are the Self. In that instant, you will also recognize and know that you were never anything else than the Self, and you will never be anything else than the Self.

Madhukar – In each attempt of self-inquiry “Who am I?”, the “me”—the “I,” the ego, the “I”-thought—dissolves, and that nothingness and silence remain as my true nature. And each time, I recognize that the “I” or “me” or the “I”-thought actually never really existed. Inquiry leads back to nothingness and silence and being what I truly am. But at times I forget this and I am back where I started.

Swamiji: Who forgets it?

Madhukar – Me! Well, here we go again! [laughter]

May I ask you another question: Somebody who sits in a cave has more time to do sadhana [spiritual practice] than somebody who has a family and a job. Has the meditator a better chance to reach enlightenment?

Swamiji: One doesn’t realize one’s true Self. The true Self is already there. One person may do a job while another person is playing. Whatever one does, it is of no use. While working, abide in your Self as if you are living in a cave. There is no outside and no inside.

Madhukar – I would like to go back to what we discussed before. Is it advisable to focus on this nothingness and wait for the next thought to arise, or is it advisable to keep inquiring as to whom this nothingness appears?

Please excuse me if I keep repeating this question; I do so intentionally. Because self-inquiry is the most important and fundamental practice for me, I need absolute clarity about its correct, practical application.

Swamiji: If you stay constantly in that nothingness, then no thoughts will arise. Only if you give up the hold on that state will something come up and take you away from it. So in that case, you have got to inquire again. If you live always with the understanding that there is only a rope, then how can a snake arise from it?

Or let us take another example. If you fill your pots full of water and you pour more and more water into them, they will not contain it. Like that, if one knows oneself, there is nothing else to know. The one who knows his own Self becomes content within himself, like a pot full of water.

Madhukar – In the waking state, the “I”-thought, the “I” notion, seems to be always present as an underlying silent sense of “I.” It is a kind of “I”- consciousness.

When I wake up in the morning, the “I”-thought slides in without being noticed because I am so used to believing that I am the body and the mind, and therefore I call them “I.” I believe that is why the “I”-thought seems to be always there. It is an ever-present feeling, although it is not always noticed.

Swamiji: To whom does this “I”-thought arise? Who is sleeping? We are all asleep. Only the sage is not asleep.

Madhukar – Okay. Let me formulate my question in a different way. It is difficult to ask the precise question. I’ll try.

What I am pointing to is how I perceive this “I”-thought or this “me.” What I am describing is how this “I”-feeling happens to Madhukar. It seems as if the “I”-feeling appears in the moment of waking up from sleep. Then the thought arises, “I want to have a cup of coffee.” It seems as if the “I”- thought and the thought of wanting a cup of coffee exist together. They become “my” thought. Is this correct?

Swamiji: To whom does all this happen? Whatever thoughts may arise, you are not that. For example, so many people in the world are thinking so many thoughts. Their thoughts are just arising by themselves. We can see all these thoughts as “just thoughts.” We can have the same kind of view regarding our own thoughts: “Whatever thoughts may arise, I am not these thoughts.” Because for the real I there is no thought. The real I is not connected with any thought. It is free from all thought. As in sleep, there is no thought.

Madhukar – Do I hear you say that thoughts are not “my” thoughts? Are thoughts just thoughts arising or appearing?

Swamiji: Thoughts appear by themselves only in waking or in dreaming. Otherwise they would need to appear in deep sleep too. Do they appear in deep sleep too?

Madhukar – No, they don’t.

Swamiji: Sleep is a miracle. In sleep there is no thought, no mind, no world, only samadhi. After waking up—as soon as the mind begins to function—the body appears and the entire manifestation begins to function.

When you have come to know who you really are, nothing affects you because you know that all is your own Self. Mind is Me. Everything is Me. All is Me. I am searching for my own Self. Take an example: There is only one gold but many different kinds of ornaments. Different kinds of ornaments are made of the same gold.

The one who does not realize his true Self thinks that the body is the true Self. The one who realizes his true Self finds that everything is his true Self. For him there is no samsara [cycle of birth and death], no nirvana [liberation from samsara] no maya [manifestation mistakenly believed to be real], no ego. All is Self. That is why this state is called the wakeful sleep. All and everything are the Self.

As Swamiji explained these things, I was overcome with tears of gratitude and bliss as a further recognition of the Self occurred. All at once my heart energy expanded and expanded until it finally burst out of all confines and fountained upward as intense light and heat that consumed my body awareness. Everything stood still. When I became aware of my body-mind self again, I found myself prostrated headlong in front of Annamalai Swami, gently touching his feet in reverence and devotion. I was unable to speak, and a deep silence permeated the room. After a long time, I sat up and resumed questioning Swamiji.

Madhukar – Listening to you, my questions don’t make sense anymore.

Swamiji: For each lock there is a key. I remember the incident when four famous pundits came to Bhagavan with a list of sixty-three questions in hand. It was a very long list. They gave the list to Bhagavan. He looked at the list. After seeing all those questions, Bhagavan asked them from whom or from where all these questions came. They just looked at each other. They looked at me, then at Bhagavan. Then they asked, “What is the answer to this question?”

Bhagavan said, “All questions have the same answer. Find out to whom the questions and the answers come. Who is the questioner? Who wants moksha [spiritual liberation]? When you know it, all questions will be answered once and for all times.” Hearing Bhagavan’s words, the pundits became silent.

Madhukar – Bhagavan seemed to have used his final weapon on the pundits. Wasn’t atma vichara, self-inquiry, called the supreme weapon by Bhagavan?

Swamiji: Yes, he called it brahmastra, the ultimate weapon. This weapon is able to defeat all other weapons. If you put armor around your body, nothing can harm your body. This is brahmakosam, the ultimate armor. Therefore if you wear the armor of your Self or if you remain in your Self, no misery, no thought—nothing—can disturb you. You get only shanti [peace] and that’s it. Shanti.

Bhagavan often used to repeat a particular teaching: He used to say about himself, “Others should not be jealous of me, because there is nobody in the world who is smaller than me. I am the smallest. I am nothing. I am less than nothing.” What he wanted to say was that one should not have an ego at all. Only a person who has that kind of humbleness can realize the Self. The one who has no ego is greater than all others. When we are nobody and no one, the Self remains. By being the Self, one is All.

On one occasion, I returned to Bhagavan when I had completed all the ashram building works he had asked me to do. Bhagavan said to me, “Don’t look back on what you have done!” From that moment onward, I have lived my life and done all my work with this selfless attitude.

A few days later, on New Year’s Eve 1993, another interview took place at the Sri Annamalai Ashram. On this occasion, only Annamalai Swami, Sunderam, and I were present.

Madhukar – On the occasion of my previous visit, I asked you for guidance regarding my self-inquiry practice. Today I would like to ask you for further guidance.

Swamiji: Don’t hesitate to ask.

Madhukar – I think I am going to repeat myself. Is that okay?

Swamiji: Ask your questions!

Madhukar – When I arrived at Arunachala, my practice of self-inquiry proceeded in the following manner:

When a thought appeared I would ask myself, “To whom does this thought appear?”

Answer: To me.

Question: Who am I?

Answer: Emptiness, nothingness. This answer expresses itself not as a word but rather as something like a feeling within myself.

Question: To whom does this emptiness appear?

Answer: To me.

Question: Who am I?

Answer: Emptiness, nothingness.

Then the next futile circle of inquiry would start again. There seemed to be no way out. As I told you, the situation was similar to a dog chasing its own tail.

Now, after having been four weeks at Arunachala, the content of the answer to the inquiry “Who am I?” seems to have changed. The same “I” that is present in the inquiry “Who am I?” stays present as the all-pervading and silent “I”—as an unspoken answer. The “I” is everywhere and in everything. Would you comment, please?

Swamiji: That is the real I.

Madhukar – At times, the perception of the I pervading everything is stronger than at other occasions. Why is that?

Swamiji: The perception is less to whom? [laughter] In fact, in the Self there is no “more” and no “less.”

Madhukar – In this I, there is neither good nor bad. In this I, is nothing but I.

Swamiji: In the days with Bhagavan, there was no such thing as good or bad. There was nothing to judge. We didn’t judge what was good and what was bad. Whatever was, was accepted.

Madhukar – I heard you say, “Hold on to the I!” You said that the all-pervading I that I have described to you is the real I. How can I know it is the real I?

Swamiji: If you don’t hold on to the real I, there will be the idea, “I am the body and the mind.” They look real. That is why it is suggested to hold on to the real I until you have become firmly established in the real I. The conclusion of meditation is to remain in your real state. But the truth is that nobody is doing meditation. All is the Self.

Madhukar – That state is not really a state, and therefore it cannot be “my state.” That state is “nobody’s state.”

Swamiji: In this state, you are not remembering and you are not forgetting anything. You are not thinking and not remembering “I am Madhukar” or “I am not Madhukar.” When you have the feeling “I am Madhukar,” you are self conscious. As long as we are referring to the body and mind, we have to meditate on the Self. Remember, all thoughts and methods regarding karma yoga [path of action], bhakti yoga [path of devotion], dhyana yoga [path of meditation], and jnana yoga [path of wisdom] are not the truth. We should not meditate on the body and on the mind but only on the Self. When we become established in the Self, there is no need to think about the Self.

Take the example of the snake and the rope.

As long as the illusion of the snake is there, the truth is not revealed. When you are fully convinced that there is only a rope, then there is not even the need to remove it.

Madhukar – When a rope is a rope there is no need for inquiry. When the rope appears to be a snake, there is a need for inquiry. Is that what you are saying?

Swamiji: To reinforce what I taught you in your first visit, I will quote a song from Bhagavan: “I am a man. And once I know that I am a man, what is the need to think that I am a man? But if I think I am somebody else or something else, then I must first come to know and to recognize that I am a man. And I then must give up that illusion to be something else.”

The vasanas—the latent tendencies, conditionings, and habits of the mind carried over from many past lives—hinder the realization of the realized state. These tendencies appear and cover the truth. That is why you must inquire, “Who am I?” and “To whom does this happen?” Such practice will irradicate the vasanas.

Madhukar – Are you saying that inquiry is essential in every moment and in every situation?

Swamiji: As long as light is lit in the house, darkness cannot enter. Likewise, as long as meditation and self-inquiry are practiced, vasanas cannot stay on. Continuous meditation is like a river. The flow of the river is always uninterrupted. When a constant flow of awareness is going on, vasanas cannot enter. This is constant meditation.

Madhukar – In a state of bliss, is it also necessary to keep inquiring, “To whom does bliss happen? Who am I?” and so on?

Swamiji: Try to inquire into happiness and you will find the same peace and quiet of the Self that is underlying both happiness and misery.

Madhukar – For many years, my understanding was that the experience of permanent bliss is the experience of the Self. Bliss or misery is experienced by the “me.” Both are experienced on the same level. How can I go beyond happiness and unhappiness?

Swamiji: Only on the level of the mind do opposites exist, like pain and pleasure, unhappiness and happiness. But in the Self there is no such thing.

Let me give you an example. Because of the eyes, you are able to see everything around you. But you cannot see your eyes with your own eyes. Even though you can’t see your own eyes, you cannot deny the existence of your eyes. You know with absolute certainty that they exist. The Self is like that. You cannot see the Self as an object, but you are the Self. Being one’s Self is jnana [wisdom]. Being the Self is knowing the Self. In that state, there is no duality. You are always That. You think that you are different from the Self, and that is the mistake. Giving up the difference is sadhana.

In the deep-sleep state, there is no difference between you and the Self. At this moment—here-now—there is also no difference between the Self and you and everything else. All is One. All is the One. All is one Self.

Madhukar – Bliss and misery don’t touch the Self. Seen from the viewpoint of the Self, they happen like a dream. In the realized state, bliss and misery are happening within awareness but without personal identification. Is that correct?

Swamiji: Ultimately you cannot divide anything. All is Self. Take the body as an example. The whole body is yours: The two legs are yours; the two hands are yours; the two eyes are yours. In bodily life, happiness and misery always coexist. It is important to meet both with equanimity. In a small baby, you can see vividly that happiness and misery merge into one.

I had one last interaction with Swamiji. I wanted to hear one more time what he had to say about the issue of gurus declaring their students enlightened, and in particular, about Papaji’s declaration of my enlightenment. I expected him to have at least some reservations about Papaji’s distinctive custom. I decided to seek from Annamalai Swami a more private answer in the intimate context of a personal letter. Thus, the following questions and answers were conveyed by mail in summer of 1994. They are set out below, along with his answers (translated by Sunderam).

Madhukar – Did Bhagavan ever declare any of his disciples enlightened?

Swamiji: As far as I know, Sri Bhagavan did not declare anybody enlightened except his mother and the cow, Lakshmi. Nevertheless, many seekers reached very high states and attained peace and maturity in his presence.

Madhukar – Do you believe that my guru, your gurubhai, Poonjaji, is enlightened?

Swamiji: Although I never met Poonjaji in person, I consider him as an enlightened being.

Madhukar – Poonjaji declared me enlightened several times. But I didn’t consider myself to be enlightened. Was Poonjaji fooling me as well as others?

Swamiji: You said in your letter that Poonjaji declared you enlightened.

Poonjaji is correct. But you did not trust and stay by his words. You moved away from the state of enlightenment and got yourself caught in the trap of the mind and its doubts. So it is not Poonjaji’s mistake. It is your mistake. Realize the tricks of the mind and be free from it.

Madhukar – I wish I could meet my real, final, and last guru in this life. How can I find him? What can I do to find him?

Swamiji: If you have the intense desire to live with a guru in whom you have total trust, that intensity will take you to a master. If you are fully ready to receive a master, the master will come to you.

At the end of 1995, I received a letter from Sunderam that contained the sad news and some of the details of Sri Annamalai Swami’s mahasamadhi. He wrote that Swamiji had not been feeling well and his body had become increasingly weak during the preceding months. Early one morning after Annamalai Swami awakened, he had asked Sunderam and a French devotee to help him sit in his armchair. As he sat there, the swami closed his eyes and seemed to go into samadhi. However, his breath soon became weaker.

Sunderam sat on the floor in front of Swamiji, and the French devotee sat in a chair behind Swamiji, holding and steadying him in a gentle embrace. There was no talk. Both devotees knew that Swamiji was leaving his body; both devotees sat in silence and with full awareness. They knew that nothing could or should be done other than what they were already doing— just being there. A short while later, Swamiji’s breathing ceased. His mahasamadhi had occurred in the early morning hours of November 9, 1995.

When I met Sunderam in Bombay in spring 1996 I asked him what he had felt or experienced just before Swami’s death, at the moment of his death, and right after his death. Sunderam said that he did not experience anything special during his guru’s passing away. There was no special transmission or energy phenomenon, he said. Swamiji died exactly in the same way he lived—ordinarily and simply. Sunderam told me that after the traditional rituals had been performed, his master’s enbalmed body was lowered in the lotus posture into the samadhi shrine that Swamiji had prepared a few years prior to his death. Sunderam said that it didn’t seem to matter to Swamiji where he sat—in a chair or in his samadhi. Death, in the sense of the ending of his attachment to the body, had happened way back in 1938 when Sri Ramana’s words, “Ananda [bliss], ananda, ananda!” had confirmed his enlightenment.

I was deeply touched by the simplicity of Annamalai Swami’s teaching and lifestyle. In fact, I was in love with him. During my conversations with him, I became immersed several times in the peaceful and blissful experience of the Self. It happened without effort. It was so easy!

Questioning Annamalai Swami repeatedly about the technique of the self-inquiry process, and my experiences of practice in his presence and under his guidance, opened up a new spiritual vista for me. Swamiji’s clarifications enabled me to directly and easily experience the Self. This ability inspired me to sing with joy and relief. A deep relaxation and tremendous satisfaction occurred in me when the understanding arose that my own Self is available anytime. In fact, I am the Self! I knew with certainty that it could perhaps be forgotten momentarily but never again would it be lost. Until my meeting with the swami, I wasn’t aware that the Self revealed itself so often during my self-inquiry practice. Like the manner in which a windshield wiper provides a clear view after pushing off rain with each swing, my thoughts now dissolved anew during each attempt of self-inquiry, revealing my true nature. My meditations now became an opportunity to directly and frequently experience—on my own! —the peace and quiet of the Self.

From my experience with Papaji, I knew first hand that the initial “pointing out” by the guru and the subsequent recognition of the Self by the seeker through self-inquiry were crucial to the awakening process. But contrary to Papaji’s teaching—and congruent with my own experience—I now was convinced that the first conscious experience of my true nature was not enough for me to be permanently established in enlightenment. I had learned from Annamalai Swami that one needs many dips into the Self through ongoing practice, perhaps over lifetimes, until one can remain constantly in and as the Self.

At one point, I had asked Annamalai Swami how many of his own disciples had become enlightened and whether he proclaimed the event of their moksha. He replied that it was up to them to discern if enlightenment had occurred and to declare so if they wanted to. He added that he didn’t know who or how many of his devotees had found freedom so far. Shouting his own enlightenment or that of others from the rooftop was not his business, he said.

What I heard from the swami made me ponder Papaji’s custom of declaring seekers enlightened. I contemplated particularly the fact that about one hundred seekers—including myself—supposedly had become enlightened in his presence!

But could this be true? I began anew to question Papaji’s claims. Why didn’t Sri Ramana declare his disciples enlightened? Why didn’t I hear about similar enlightenment success rates of other teachers of Advaita Vedanta or of other traditions in India, or in other schools such as Tibetan Buddhism and Zen?

Perhaps I would not have needed to struggle so much, had Papaji only told me that what I had experienced was a recognition of the Self and not the final experience of enlightenment. Then my odyssey would probably have unfolded in a rather different fashion. It is quite possible that I would have relaxed and kept practicing with Papaji until his last day on Earth.

My meetings with Annamalai Swami convinced me that final enlightenment in my case simply required more practice. I was ready to do just that. By the same token, I was still not ready to let go of the concept that enlightenment is a Big Bang event that in its culminating moment is complete once and for all. I still believed in a sudden transformation after which every one of my perceptions would be different from then on, rather than a continuous vigilance and expanded awareness grounded in my essential nature. In spite of my own experience, part of me still hoped that Papaji was somehow right in his assessment of my enlightenment and that it merely remained mysteriously veiled. And I still believed that the spiritual power of a guru could be synchronized with my consciousness and act with the aid of practice as a catalyst for awakening. By my simply lifting the veil, enlightenment would remain. Driven by such hope and possibility, my odyssey continued.

-Berthold Madhukar Thompson

Excerpt from The Odyssey of Enlightenment: Rare Interviews with Enlightened Teachers of Our Time, Chapter 5

Excerpt from The Odyssey of Enlightenment: Rare Interviews with Enlightened Teachers of Our Time, Chapter 5

See the post from chapter 8: You have to Work for the Fulfillment of Your Destiny.